Net-Zero U.S. Cities and Communities are Here Already

By Jonathan Rowe

Today, more than half of the world’s population calls a city home. And over the next few decades, that number is projected to rise.

From an environmental perspective, cities are already responsible for the majority of the planet’s energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. To meaningfully battle climate change and stay within our carbon budget, getting things right at the urban scale is critical.

Internet of Things (IoT) visionaries imagine a future where a “smart” electricity grid communicates bidirectionally with smart buildings wired with sophisticated sensing and controls technology. With this kind of setup, net-zero energy buildings—hyper-efficient structures that produce as much energy from renewable sources as they consume from the utility annually—could easily be the norm. But this is pretty far out on the horizon.

Creating a net-zero building today isn’t easy, especially on a tight budget. No surprise then that cities such as Masdar in Abu Dhabi have backpedaled on their lofty net-zero ambitions due to economic and technological constraints. If urban areas built from scratch on oil money can’t get to net zero, can existing communities and cities? And if so, what lessons from today’s net-zero craze can guide the future of energy-neutral cities?

Today’s Trend Toward Zero.

From federal policy to state legislation to voluntary certifications and global calls-to-action, net-zero energy has become a rallying cry for how we might make a huge difference combating climate change by targeting buildings. Buildings are “hot spots” that account for about a third of the world’s greenhouse gases.

Technology advances are helping. More efficient heating, cooling, and lighting systems—coupled with better building envelopes and more powerful solar panels—make it possible to deliver a low- or zero-energy building with less effort than a decade ago. And designers are demonstrating that futuristic technology isn’t required to get there. Off-the-shelf systems work fine.

Consider the 222,000 square foot National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) Research Support Facility. Sure, there are a few fancy features (ever hear of a thermal storage labyrinth?), but careful siting, orientation, and façade strategies that bring daylight into the workspaces did the heavy lifting for energy conservation. No rocket science here.

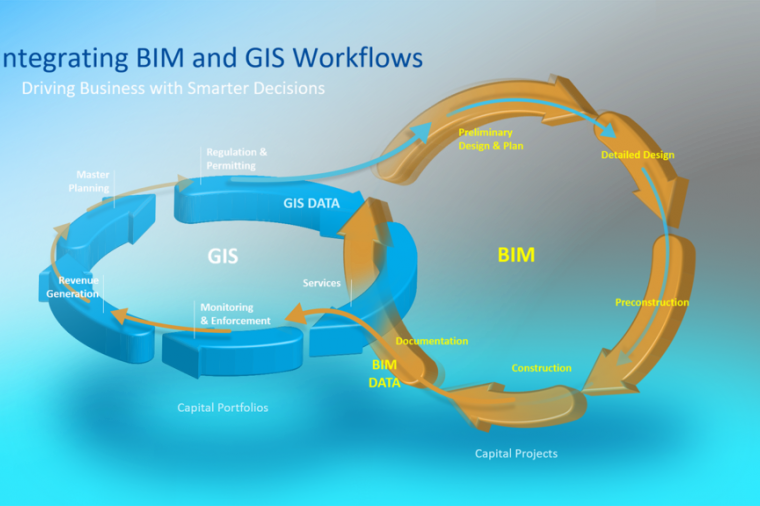

What is different is the radical approach to collaboration compared to traditional ways of building. Architects were once hailed as “master builders,” the central brains behind many timeless structures we still revere today. But in today’s world of hyper-green building design, there’s too much complexity for any one person—architects included—to have the expertise to deliver a net-zero building solo.

Sustainability can be a no-brainer.

For NREL, the architects transitioned to “masters of collaboration,” synthesizing and corralling information from a web of experts—engineers, builders, and various consultants. With that data, they could deliver on functional, programmatic, and performance goals by continuously assessing trade-offs throughout the design process. The building community calls this “integrative design” and recognizes it’s difficult given entrenched mindsets and traditions.

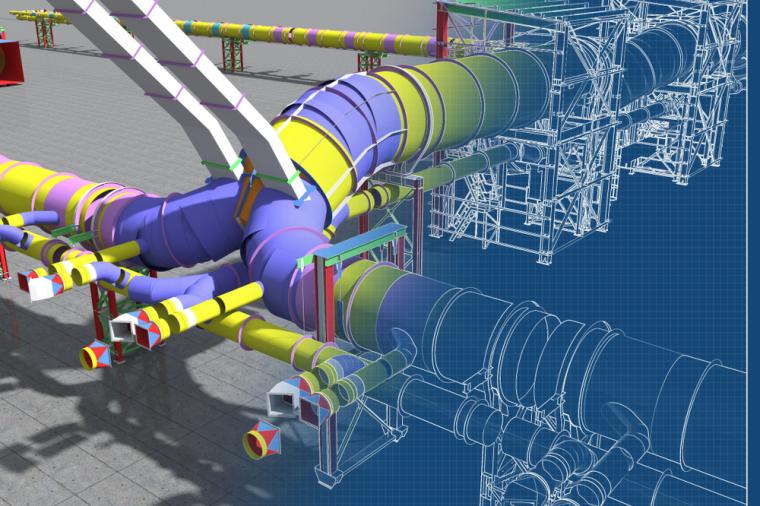

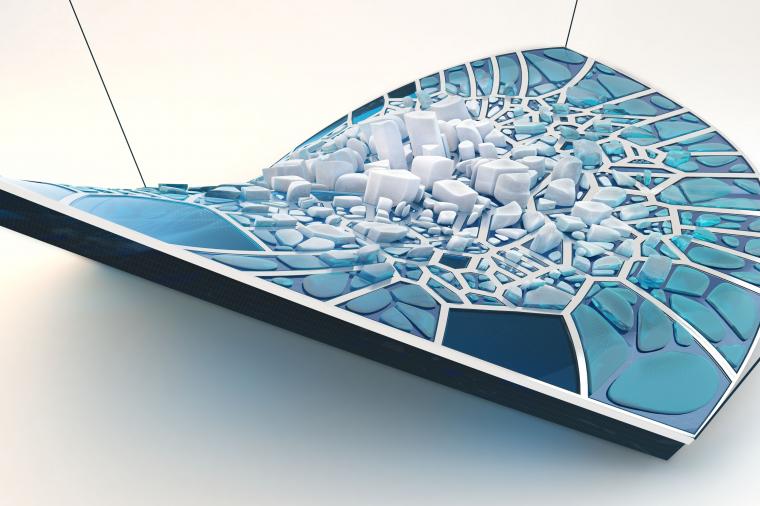

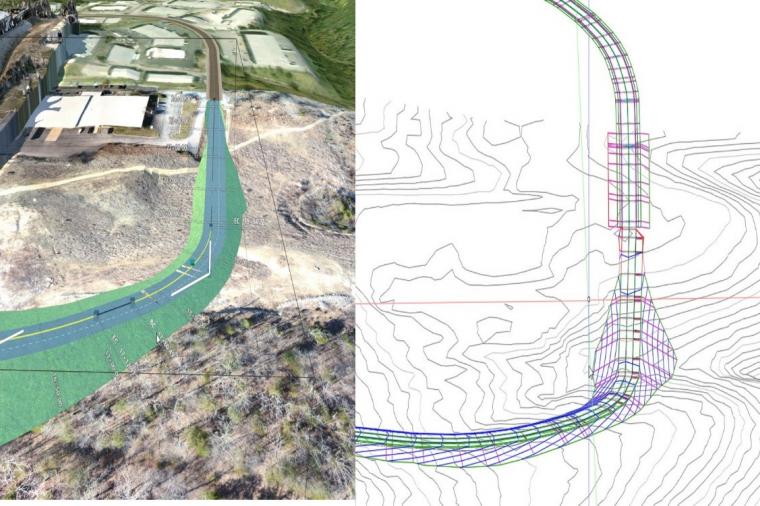

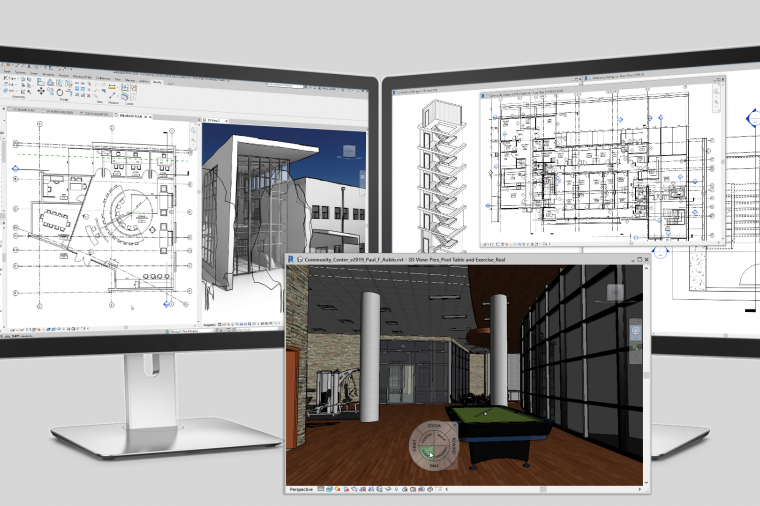

Virtual models are key for success in achieving net zero. Instead of 2D drawings, 3D models are serving more and more as a team’s single source of truth for design and construction. The advantages of designing, coordinating, optioning, and exploring in 3D are manifold.

Simulations of performance become critically important to get right for net-zero buildings. Given the inherent difficulties with predicting human behavior, how people end up using a space ends up having dramatic effects on the energy bill. Engineers for the David and Lucile Packard Foundation headquarters invested more time than usual to understand nuances of use over time from the owner. The extra effort paid off, and the headquarters is the largest certified net-zero energy building so far.

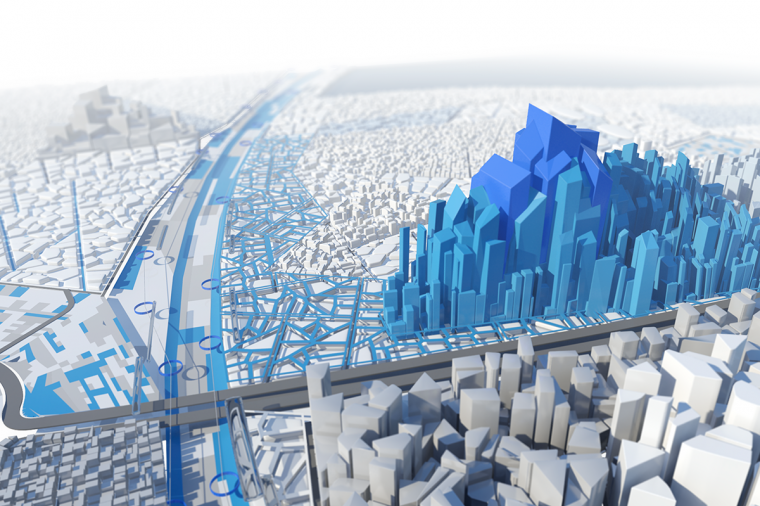

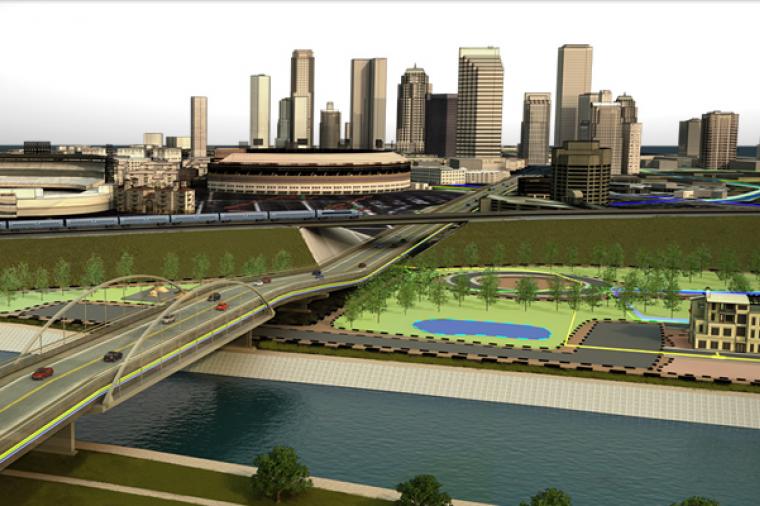

Beyond Buildings: Scaling Up Net Zero. On their own, individual net-zero buildings are commendable feats of design, engineering, construction, and operations. But to really make a difference combating climate change, they need to scale up fast. What do these building trends mean for cities? Can thinking bigger make net zero more cost-effective by leveraging resources among clusters of buildings and their shared infrastructure?

In a 2014 report, the New Buildings Institute tracked a growing pack of projects—with the majority of square footage in the education sector—reaching for net-zero energy. Most were individual buildings, but some were proving that campuses, neighborhoods, and even entire communities could capture efficiencies of scale that one-off buildings can’t.

The largest net-zero community in the U.S. is West Village, a mixed-use campus neighborhood at UC Davis, designed to house 3,500 students, staff, and families once complete. Phase one has been occupied for over a year and is close to meeting its net-zero design target. Technological glitches and higher-than-expected demand from apartment dwellers’ plugged-in gadgets held it back from claiming energy-neutral status.

UC Davis isn’t alone in making a strong environmental statement. With 673 signatories, the American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment underscores the magnitude of buy-in from the education sector for targeting carbon neutrality. Universities are essentially microcosms of cities—ideal testing grounds for showing how carbon neutrality can happen at a municipal scale—with net-zero building principles being a big part of the overall strategy.

The University of Arizona partnered with Ameresco—the nation’s largest independent energy services solutions provider—and the Rocky Mountain Institute to plan for full-on campus-wide carbon neutrality by 2025. They plan to reduce energy demand using a holistic approach toward efficient buildings, low-carbon transportation, and increased renewable energy.

Exploring net zero extends beyond university campuses. FortZED is a zero-energy district combining the Colorado State University campus and part of downtown Fort Collins. It combines efficiency measures across a diverse mix of building types, and bringing online new renewable generation.

Exploring net zero extends beyond university campuses. FortZED is a zero-energy district combining the Colorado State University campus and part of downtown Fort Collins. It combines efficiency measures across a diverse mix of building types, and bringing online new renewable generation.

FortZED is a compelling example of partnering with a utility to test the feasibility of creating net-zero districts by orchestrating many small, distributed renewable generation systems—including wind, solar panels, and biomass—bidirectionally across the electricity grid. That’s impressive, considering our energy grid is designed for one-way delivery.

With more U.S. cities planning 2030 Districts, utilities have to get involved. The ultimate effect of net-zero energy districts affects their business models. In a district where everyone’s energy meter nets out to zero, who pays for the transmission and distribution systems that keep the lights on?

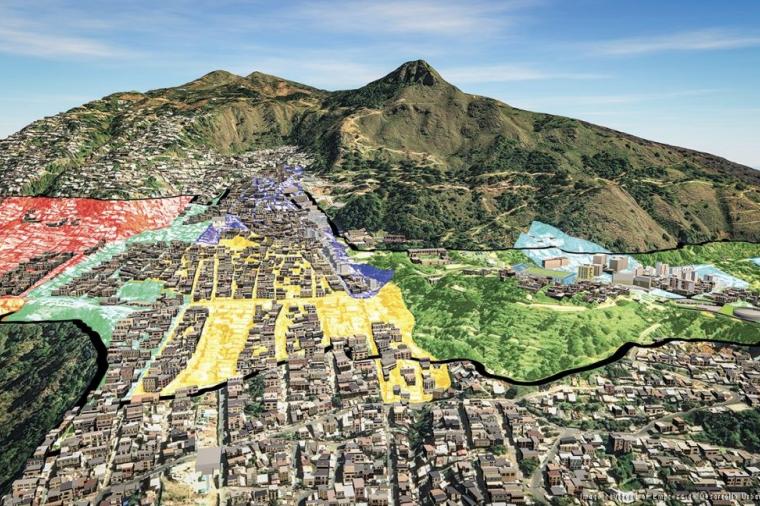

And to complicate things at the city scale, focusing on building energy use alone is just one piece of integrated planning that should address impacts from transportation emissions, water conveyance, and waste infrastructure. Net-zero cities will rely on a new breed of synthesist—systems thinkers adept in tackling large-scale technical, managerial, and societal challenges—to bring these visionary seeds to the cities most of us will, sooner or later, call home.

Jonathan Rowe

Jonathan Rowe manages content strategy for Autodesk’s Sustainability Solutions team. In his life before Autodesk, Jonathan became an expert in green design while pursuing a career in architecture. When he’s not geeking out to high performance buildings and green manufacturing, there’s a good chance he’s enjoying sunshine in Dolores Park, practicing his handstand at a favorite yoga studio, or memorizing a challenging Bach Invention on his piano.

This article originally appeared on Autodesk’s Line//Shape//Space, a site dedicated to inspiring designers and creators.