Public Building Simulation: Analyzing Performance Without Breaking Ground

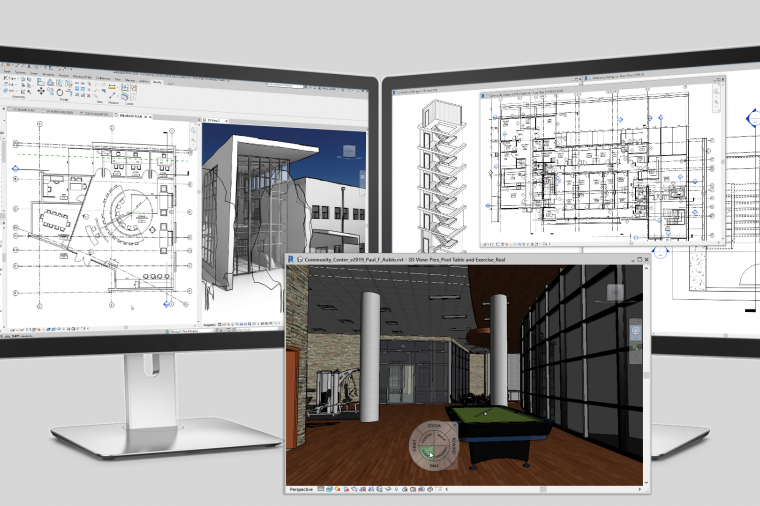

Today’s architects and engineers can now analyze building performance early in the design stage thanks to 3D building performance simulation and finite element analysis.

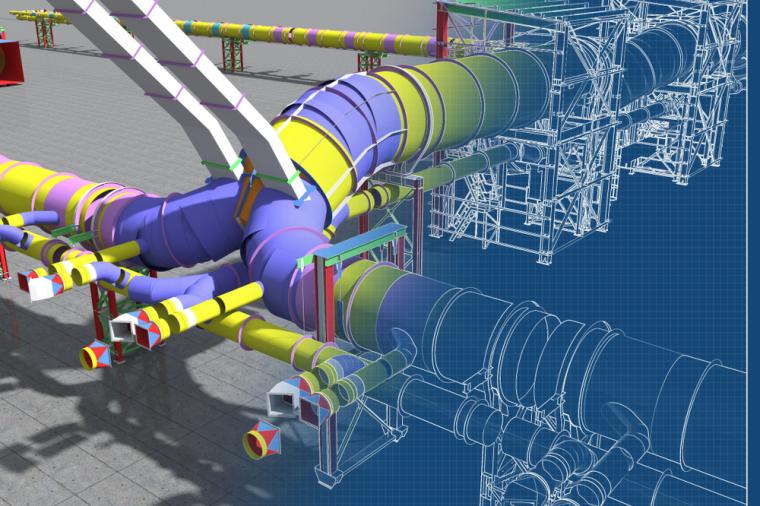

Simulation tools allow them to effectively predict building energy performance, sustainability, and green features such as daylighting, as well as performance attributes such as airflow for heating and cooling needs, including computational fluid dynamics for buildings (such as data centers that require constant cooling). Thanks to the complexity of today’s building projects, simulation is becoming de rigueur for government and even private owners whose buildings must perform as advertised. Engineers and designers are being required to provide simulation proof that the design will work and that the energy consumption meets certain requirements.

Whole-building simulation and analysis programs have been assisting engineers for decades, but many were complicated and required expert-level training to be used by anyone but expert-level software engineers. Now, programs such as Autodesk Ecotect Analysis and Bentley AECOsim give users the power of simulation with the simplicity of familiar user interfaces and ranking tools. The U.S. Department of Energy provides a list of programs for energy simulation, load calculation, renewable energy, retrofit analysis, and sustainability through its Building Energy Software Tools Directory.

I was able to see up close just how much building simulation and CFD technology can predict actual building performance when I visited the Center for Sustainable Landscapes, a $15-million, 24,350-square-foot, off-the-grid office building and educational center on the grounds of Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens in Pittsburgh.

Opened in 2011, the net-zero center actually generates electricity from solar panels that feed power back into the grid and boasts an impressive combination of the latest green building technologies and traditional building operations features such as underfloor air distribution and glass exterior curtain wall to allow natural daylighting. So many technologies working together simply had to be simulated and validated before ground was broken.

“With this design, you must seal the building more carefully using this much glass, so that there are no pathways, like ducts, causing thermal or air infiltration ‘leaks’ into the building that would reduce your efficiency,” explains Alan Traugott, principal at Pittsburgh-based CJL Engineering and the lead MEP (mechanical, electrical, and plumbing) engineer on the project. “The different construction trades had to be coordinated for construction as well. Using underfloor air distribution on this project, we had to make sure that the curtain wall and exterior walls were not creating places for condensation inside. We had to eliminate air gaps and keep a tight air barrier. It looks simple in so many ways until you realize how much thought went into each piece.”

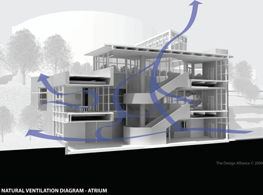

Computational fluid dynamic analysis was performed to decisively show how natural ventilation air would flow in the completed building. ANSYS Airpak for building simulations was used as the CFD software by CJL. Based on that analysis, it was decided that double-opening windows on office/classroom floors provided the best airflow deep into the space for those floors, allowing air to come in the bottom and go out the top. That was the most efficient circulation pattern. “Air has an unrestricted flow path that works with air’s natural buoyancy,” Traugott explains.

The Center for Sustainable Landscapes was recently certified LEED Platinum and is part of the Living Building 2.0 Challenge.

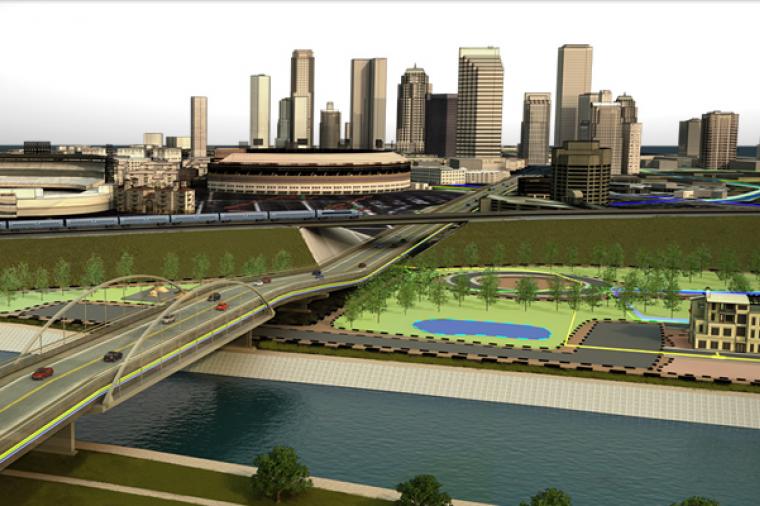

Building simulation is not just for sustainable design and MEP design. The Department of Homeland Security is in the process of consolidating its entire capital region operations into the St. Elizabeth’s Campus in Washington, DC. This secure campus will bring together executive leadership, operational management, and staff in an effort to improve communication and coordination, as well as save government resources. The $3.4-billion, 4.5-million-square-foot DHS Campus project represents the federal government’s first significant presence in the District of Columbia’s neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River, and, after its completion in 2016, will bring together up to 14,000 of the region’s 26,000 Department of Homeland Security employees, now scattered in 70 buildings at 40 different sites.

Instead of using a simulation program for building performance or sustainability analysis and prediction, property developer Jones Lang LaSalle and campus architect HOK used Beck Technology’s DProfiler to develop cost models for JLL’s feasibility study of the existing St. Elizabeth’s Campus in 2008. Seven different design concepts, all including multiple phases of construction, historical preservation, anti-force protection, renovation, and rehabilitation were expressed in the DProfiler model created for the study. Planning and best use of federal dollars were able to be gleaned from the JLL/HOK analysis and simulation.

“We were brought onboard to assist with their [HOK’s] conditions analysis, as well as the seven new concepts they came up with on how to repurpose that campus for DHS,” says Brent Pilgrim, director of consulting services at Beck Technology. “We used DProfiler to capture not just all the costs associated with the buildings that would be renovated—there are 100 different buildings on the St. Elizabeth’s Campus—but also which ones would be demolished and what costs were associated with that.”

In July, the U.S. Coast Guard became the first agency to fully move into the St. Elizabeth’s Campus. The rest of the DHS will gradually take occupancy by 2016.

No matter what your project’s needs might be, 3D simulation can give you insight into design alternatives and building performance.

For more on why going green is good, check out Save Money and the Planet: Build Green [Infographic].

By Jeff Yoders

This article was originally published on Line/Shape/Space, an official Autodesk blog, and is reprinted here with minor modifications and with kind permission.

Featured image courtesy of Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens.