Looking at MS4 Through an Economic Development Lens

As local and state governments grapple with changing environmental stormwater regulations, some face lawsuits over their stormwater policies. But others, approaching stormwater control from an economic development angle, are finding MS4 solutions that do more than just meet EPA regulations; they also help build stronger communities.

In Sarasota County, Fla., for instance, county officials are finding success with stormwater projects that partner up front with economic development and other agencies. “Stormwater 3.0 will really be about using stormwater budgets to attract development,” says Lisa Nisenson, the greenhouse gas coordinator in Sarasota County. “There’s a convergence of several forces going on. To meet environmental standards, we’re going to have higher post-construction requirements related to stormwater. But if you want to support the small businesses that populate a downtown or other commercial area, you don’t want to go to each building and give them costly requirements and say, ‘you’re on your own.’” Instead, Sarasota County is working to incorporate stormwater best practices with other neighborhood redevelopment projects.

In Englewood, a small city within Sarasota County, the county government recently undertook a 10-block retrofit project on Dearborn Street, touted as America’s first “Green Main Street.” Rather than working separately from the zoning, road, and other involved departments, stormwater professionals were involved from the beginning. Nisenson recommended low-impact design techniques including pervious pavers and bioswales, which solve potential stormwater problems while achieving the look that designers wanted.

“The first phase of the project featured beautification and landscaping, new wayfinding signs and a lighting plan for enhancing the pedestrian-friendly older downtown,” Nisenson says. “Economic development and stormwater management were a one-two punch for retrofit, and a good example of identifying and using public right of way for stormwater control. Dearborn Street also houses many small businesses, so County-supplied stormwater management is an economic development strategy as well.”

Sarasota is approaching another project, the Fruitville Initiative, in a similar manner. Fruitville is one of the remaining tracts of undeveloped properties inside the Urban Service Boundary. “The 420-acre site is owned by five private property owners with additional land controlled by the County,” Nisenson says. “The land can be accessed by a highway interchange, but the development potential could not be realized without a major flood mitigation project sponsored by Sarasota on a site called the Celery Fields. Thus, the public-private partnership is composed of a County-sponsored water management project and a mixed-use employment center.”

In Englewood, a small city within Sarasota County, the county government recently undertook a 10-block retrofit project on Dearborn Street, touted as America’s first “Green Main Street.” Rather than working separately from the zoning, road, and other involved departments, stormwater professionals were involved from the beginning. Nisenson recommended low-impact design techniques including pervious pavers and bioswales, which solve potential stormwater problems while achieving the look that designers wanted.

“The first phase of the project featured beautification and landscaping, new wayfinding signs and a lighting plan for enhancing the pedestrian-friendly older downtown,” Nisenson says. “Economic development and stormwater management were a one-two punch for retrofit, and a good example of identifying and using public right of way for stormwater control. Dearborn Street also houses many small businesses, so County-supplied stormwater management is an economic development strategy as well.”

Sarasota is approaching another project, the Fruitville Initiative, in a similar manner. Fruitville is one of the remaining tracts of undeveloped properties inside the Urban Service Boundary. “The 420-acre site is owned by five private property owners with additional land controlled by the County,” Nisenson says. “The land can be accessed by a highway interchange, but the development potential could not be realized without a major flood mitigation project sponsored by Sarasota on a site called the Celery Fields. Thus, the public-private partnership is composed of a County-sponsored water management project and a mixed-use employment center.”

One reason Sarasota County was prepared to partner with other local agencies on projects like Englewood and Fruitville is because its water management professionals have been working for the past several years to develop a low-impact development (LID) manual. The trial and error that has been part of working on that manual prepared water management officials to present workable ideas ready to be incorporated into the retrofit projects.

“Our manual has been less of a final product and more of a vehicle to engage a wider community through ongoing outreach and improvement,” Nisenson says. “Perhaps the best application has been to narrow down a list of the best BMPs (best management practices) and really pay attention to those practices. In the beginning we were looking for practices from a larger menu, but over time found some practices apply best. I always had heartburn with menus, because they were unfocused, unprioritized and in the end resulted in localities picking those BMPs that were easiest to implement rather than those that most effectively addressed the stormwater-related stressors.”

For Sarasota County, some of the practices with the best applicability have been (1) pervious pavers, (2) cisterns and rain barrels and (3) bioswales. “Pervious pavers caught the interest of local landowners and developers because they can reduce costs down the road,” Nisenson says. “For example, a parking lot repair now requires only taking up those pavers above the damaged areas instead of repaving the entire lot. On a recent public road project, pervious pavers had an initial higher cost for materials, but eliminated the need for two ponds. One of the lessons is that we need to be creative about presenting multiple budgets to show the complete investment and maintenance picture.”

While the county’s LID manual will likely add new BMPs in the future, for now, “we find that a focus can help contractors and maintenance crews,” Nisenson adds. “And it also means we can focus on developing metrics and training local developers and landscaping companies.”

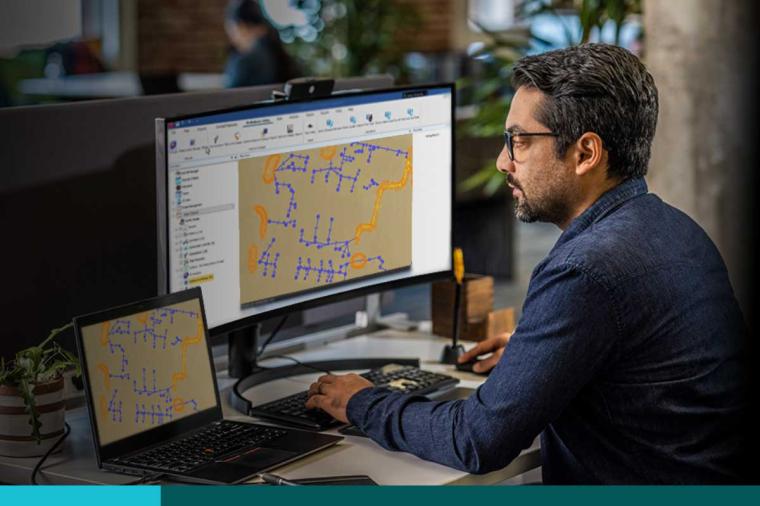

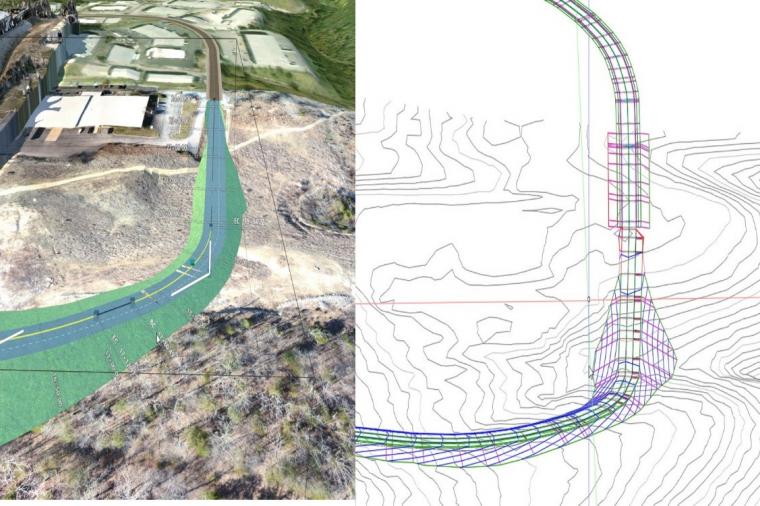

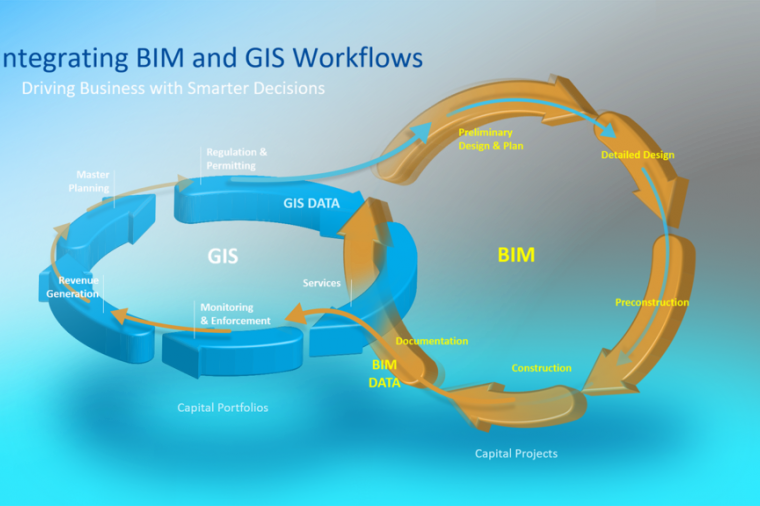

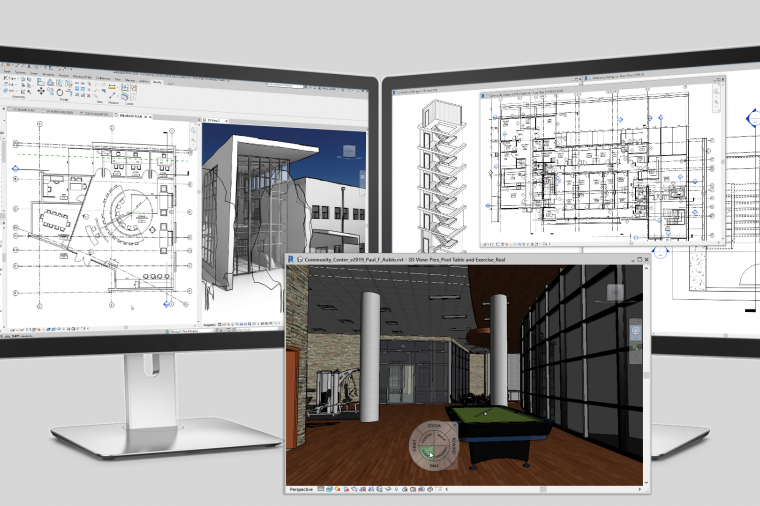

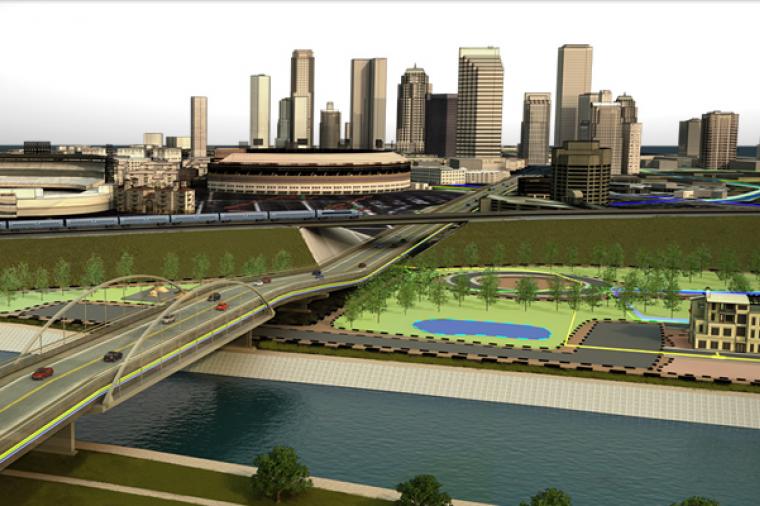

Design software solutions, such as Civil 3D from Autodesk, are also important enablers of low impact development projects. With Civil 3D engineers can incorporate GIS data into the design environment to avoid pollutant condemnation by analyzing the lay of the land during the pre-design/build phase.

[caption id="attachment_1572" align="aligncenter" width="458"]

One reason Sarasota County was prepared to partner with other local agencies on projects like Englewood and Fruitville is because its water management professionals have been working for the past several years to develop a low-impact development (LID) manual. The trial and error that has been part of working on that manual prepared water management officials to present workable ideas ready to be incorporated into the retrofit projects.

“Our manual has been less of a final product and more of a vehicle to engage a wider community through ongoing outreach and improvement,” Nisenson says. “Perhaps the best application has been to narrow down a list of the best BMPs (best management practices) and really pay attention to those practices. In the beginning we were looking for practices from a larger menu, but over time found some practices apply best. I always had heartburn with menus, because they were unfocused, unprioritized and in the end resulted in localities picking those BMPs that were easiest to implement rather than those that most effectively addressed the stormwater-related stressors.”

For Sarasota County, some of the practices with the best applicability have been (1) pervious pavers, (2) cisterns and rain barrels and (3) bioswales. “Pervious pavers caught the interest of local landowners and developers because they can reduce costs down the road,” Nisenson says. “For example, a parking lot repair now requires only taking up those pavers above the damaged areas instead of repaving the entire lot. On a recent public road project, pervious pavers had an initial higher cost for materials, but eliminated the need for two ponds. One of the lessons is that we need to be creative about presenting multiple budgets to show the complete investment and maintenance picture.”

While the county’s LID manual will likely add new BMPs in the future, for now, “we find that a focus can help contractors and maintenance crews,” Nisenson adds. “And it also means we can focus on developing metrics and training local developers and landscaping companies.”

Design software solutions, such as Civil 3D from Autodesk, are also important enablers of low impact development projects. With Civil 3D engineers can incorporate GIS data into the design environment to avoid pollutant condemnation by analyzing the lay of the land during the pre-design/build phase.

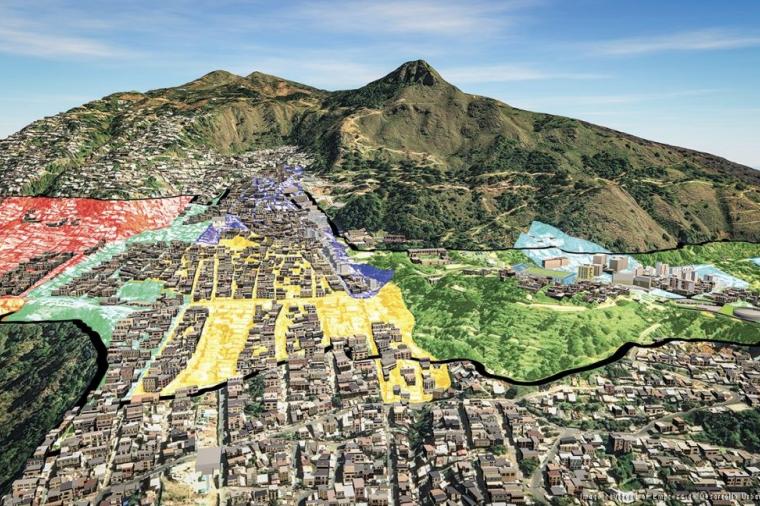

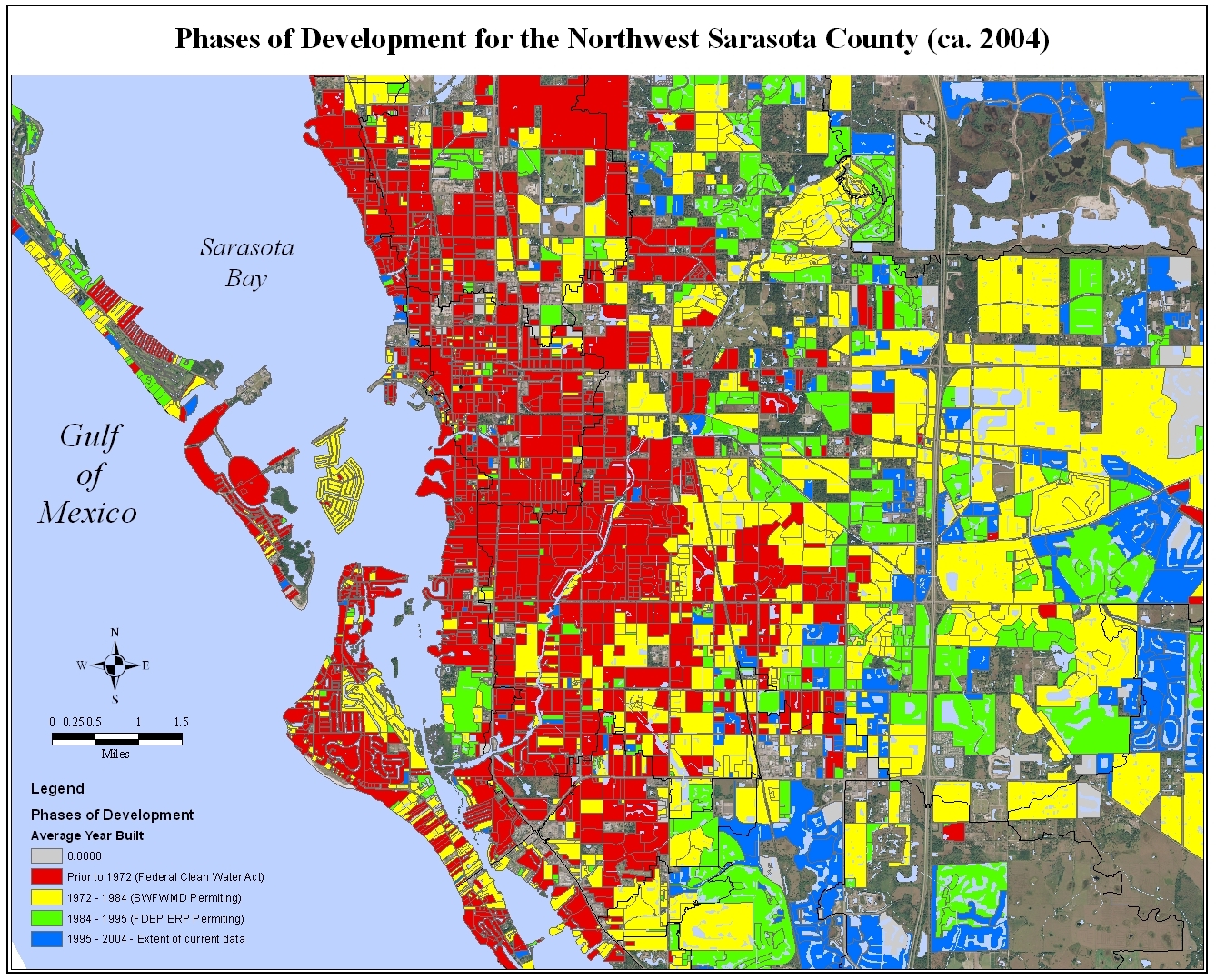

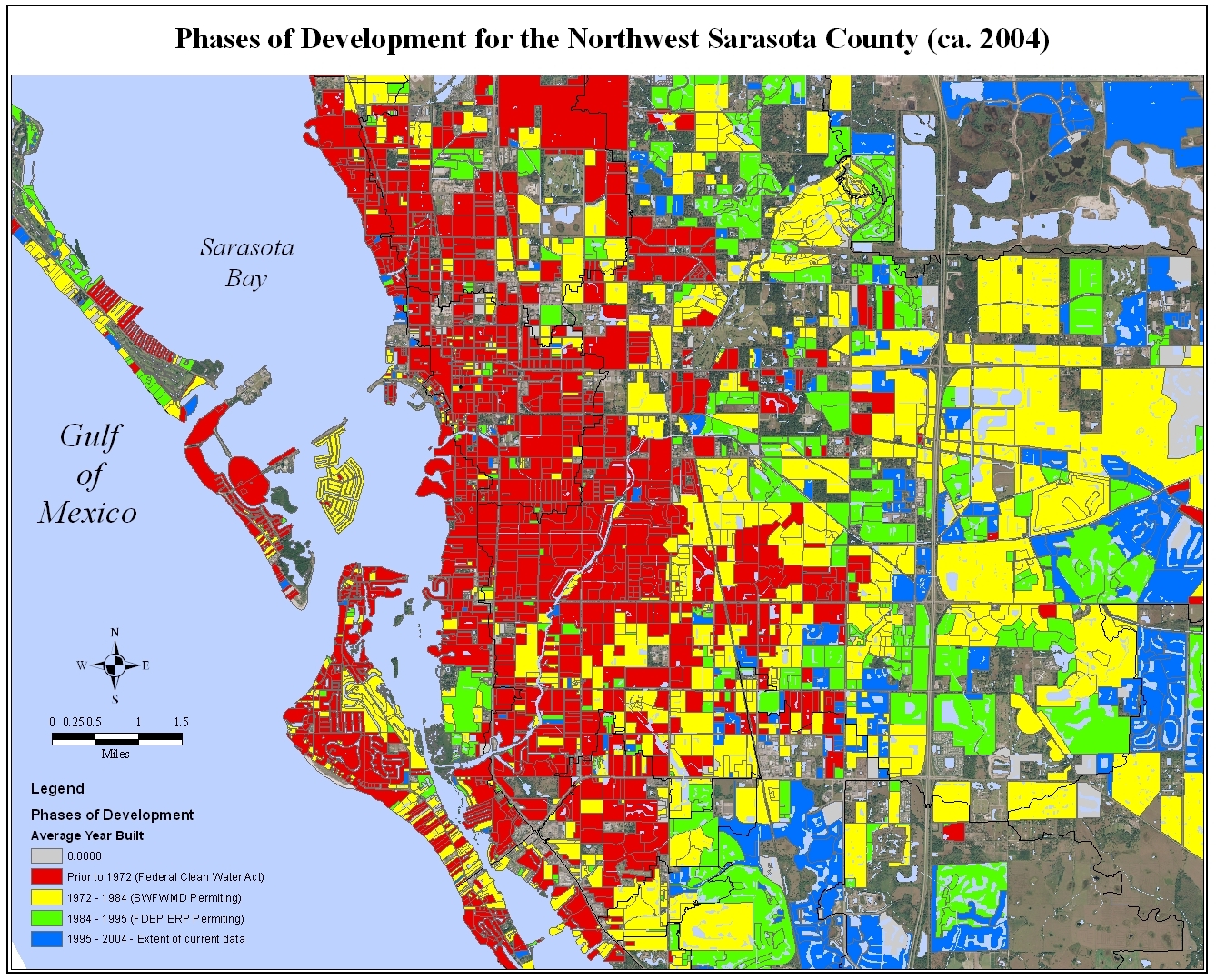

[caption id="attachment_1572" align="aligncenter" width="458"] Older pre-Clean Water Act parcels can be seen in red, and later Florida rules in yellow (1972 – 1984)[/caption]

Older pre-Clean Water Act parcels can be seen in red, and later Florida rules in yellow (1972 – 1984)[/caption]

In Englewood, a small city within Sarasota County, the county government recently undertook a 10-block retrofit project on Dearborn Street, touted as America’s first “Green Main Street.” Rather than working separately from the zoning, road, and other involved departments, stormwater professionals were involved from the beginning. Nisenson recommended low-impact design techniques including pervious pavers and bioswales, which solve potential stormwater problems while achieving the look that designers wanted.

“The first phase of the project featured beautification and landscaping, new wayfinding signs and a lighting plan for enhancing the pedestrian-friendly older downtown,” Nisenson says. “Economic development and stormwater management were a one-two punch for retrofit, and a good example of identifying and using public right of way for stormwater control. Dearborn Street also houses many small businesses, so County-supplied stormwater management is an economic development strategy as well.”

Sarasota is approaching another project, the Fruitville Initiative, in a similar manner. Fruitville is one of the remaining tracts of undeveloped properties inside the Urban Service Boundary. “The 420-acre site is owned by five private property owners with additional land controlled by the County,” Nisenson says. “The land can be accessed by a highway interchange, but the development potential could not be realized without a major flood mitigation project sponsored by Sarasota on a site called the Celery Fields. Thus, the public-private partnership is composed of a County-sponsored water management project and a mixed-use employment center.”

In Englewood, a small city within Sarasota County, the county government recently undertook a 10-block retrofit project on Dearborn Street, touted as America’s first “Green Main Street.” Rather than working separately from the zoning, road, and other involved departments, stormwater professionals were involved from the beginning. Nisenson recommended low-impact design techniques including pervious pavers and bioswales, which solve potential stormwater problems while achieving the look that designers wanted.

“The first phase of the project featured beautification and landscaping, new wayfinding signs and a lighting plan for enhancing the pedestrian-friendly older downtown,” Nisenson says. “Economic development and stormwater management were a one-two punch for retrofit, and a good example of identifying and using public right of way for stormwater control. Dearborn Street also houses many small businesses, so County-supplied stormwater management is an economic development strategy as well.”

Sarasota is approaching another project, the Fruitville Initiative, in a similar manner. Fruitville is one of the remaining tracts of undeveloped properties inside the Urban Service Boundary. “The 420-acre site is owned by five private property owners with additional land controlled by the County,” Nisenson says. “The land can be accessed by a highway interchange, but the development potential could not be realized without a major flood mitigation project sponsored by Sarasota on a site called the Celery Fields. Thus, the public-private partnership is composed of a County-sponsored water management project and a mixed-use employment center.”

One reason Sarasota County was prepared to partner with other local agencies on projects like Englewood and Fruitville is because its water management professionals have been working for the past several years to develop a low-impact development (LID) manual. The trial and error that has been part of working on that manual prepared water management officials to present workable ideas ready to be incorporated into the retrofit projects.

“Our manual has been less of a final product and more of a vehicle to engage a wider community through ongoing outreach and improvement,” Nisenson says. “Perhaps the best application has been to narrow down a list of the best BMPs (best management practices) and really pay attention to those practices. In the beginning we were looking for practices from a larger menu, but over time found some practices apply best. I always had heartburn with menus, because they were unfocused, unprioritized and in the end resulted in localities picking those BMPs that were easiest to implement rather than those that most effectively addressed the stormwater-related stressors.”

For Sarasota County, some of the practices with the best applicability have been (1) pervious pavers, (2) cisterns and rain barrels and (3) bioswales. “Pervious pavers caught the interest of local landowners and developers because they can reduce costs down the road,” Nisenson says. “For example, a parking lot repair now requires only taking up those pavers above the damaged areas instead of repaving the entire lot. On a recent public road project, pervious pavers had an initial higher cost for materials, but eliminated the need for two ponds. One of the lessons is that we need to be creative about presenting multiple budgets to show the complete investment and maintenance picture.”

While the county’s LID manual will likely add new BMPs in the future, for now, “we find that a focus can help contractors and maintenance crews,” Nisenson adds. “And it also means we can focus on developing metrics and training local developers and landscaping companies.”

Design software solutions, such as Civil 3D from Autodesk, are also important enablers of low impact development projects. With Civil 3D engineers can incorporate GIS data into the design environment to avoid pollutant condemnation by analyzing the lay of the land during the pre-design/build phase.

[caption id="attachment_1572" align="aligncenter" width="458"]

One reason Sarasota County was prepared to partner with other local agencies on projects like Englewood and Fruitville is because its water management professionals have been working for the past several years to develop a low-impact development (LID) manual. The trial and error that has been part of working on that manual prepared water management officials to present workable ideas ready to be incorporated into the retrofit projects.

“Our manual has been less of a final product and more of a vehicle to engage a wider community through ongoing outreach and improvement,” Nisenson says. “Perhaps the best application has been to narrow down a list of the best BMPs (best management practices) and really pay attention to those practices. In the beginning we were looking for practices from a larger menu, but over time found some practices apply best. I always had heartburn with menus, because they were unfocused, unprioritized and in the end resulted in localities picking those BMPs that were easiest to implement rather than those that most effectively addressed the stormwater-related stressors.”

For Sarasota County, some of the practices with the best applicability have been (1) pervious pavers, (2) cisterns and rain barrels and (3) bioswales. “Pervious pavers caught the interest of local landowners and developers because they can reduce costs down the road,” Nisenson says. “For example, a parking lot repair now requires only taking up those pavers above the damaged areas instead of repaving the entire lot. On a recent public road project, pervious pavers had an initial higher cost for materials, but eliminated the need for two ponds. One of the lessons is that we need to be creative about presenting multiple budgets to show the complete investment and maintenance picture.”

While the county’s LID manual will likely add new BMPs in the future, for now, “we find that a focus can help contractors and maintenance crews,” Nisenson adds. “And it also means we can focus on developing metrics and training local developers and landscaping companies.”

Design software solutions, such as Civil 3D from Autodesk, are also important enablers of low impact development projects. With Civil 3D engineers can incorporate GIS data into the design environment to avoid pollutant condemnation by analyzing the lay of the land during the pre-design/build phase.

[caption id="attachment_1572" align="aligncenter" width="458"] Older pre-Clean Water Act parcels can be seen in red, and later Florida rules in yellow (1972 – 1984)[/caption]

Older pre-Clean Water Act parcels can be seen in red, and later Florida rules in yellow (1972 – 1984)[/caption]

This blog entry was submitted by Nancy Mann Jackson. Nancy Mann Jackson is a freelance journalist who writes regularly about local government and sustainability issues. Learn more about her at www.nancyjackson.com.

Related Articles

What is an MS4? ‘MS4 for Dummies’ and Dana Probert of Autodesk Help Shine Some Light