[acronym] investigates a project that protects urban forests in downtown San Francisco using open source geospatial software.

So you always wanted to be a forest ranger, but can’t imagine life without take-out food and lattes? One way to live out your fantasy is to care for an urban forest.

Though it sounds like an oxymoron, urban forestry is a serious science. Urban foresters plant, maintain and care for street and median trees, making sure they survive and thrive. City trees must cope with a daily onslaught of car exhaust and dog visits, sidewalk encroachments and the occasional parking mishap. Through it all, urban trees deliver substantial economic, environmental and aesthetic benefits.

By providing shade, a tree lowers the energy costs of nearby buildings; by absorbing air pollutants, it improves local air quality; by absorbing rain, it reduces the burden on the sewer and stormwater systems; by sequestering carbon dioxide, it can help a city meet its climate protection goals. Trees also increase property value and provide habitat for birds and other wildlife. When you add it all up, urban trees are an excellent investment; studies show that they give back $1.89 in benefits for every $1 spent on forest programs in Modesto, California, $2 for the same amount in Chicago, Illinois, and $2.18 in Fort Collins, Colorado.

Little wonder, then, that many cities are planting new trees as fast as they can. At the time of publication, San Francisco had added 5000 trees to its 100,000-specimen forest, for each of the past three years. This rapid increase in the number of trees pushed the limits of the Department of Public Works’ Bureau of Urban Forestry’s (BUF) existing tree database. Although each entry contains many useful details about a tree (its species, when it was planted and by whom, maintenance dates), the database is incomplete and hard to use. Moreover, it can’t exchange data with the Bureau’s community-based ally, Friends of the Urban Forest (FUF). FUF is a local non-profit that helps residents choose, plant and care for trees in their neighborhood. FUF’s database is so old and clunky that it loses data every time it’s updated, but contains critical information about trees planted on city property by individuals and neighborhoods.

Enter Amber Bieg, a development officer for FUF who had organized a tree-mapping project in Los Angeles a few years ago. Bieg knew the value of involving the community in gathering tree data, but also recognized that any tree map must be kept current in order to be useful to the city and the public. Her vision? Create a Web-based mapping tool that the public can use to update information about their favorite trees, even adding a photo or stories. Let people search for the trees in their neighborhood, or check out a particular species before planting one. Make it easy for them to understand the benefits provided by their local tree or the forest as a whole. Get San Franciscans hooked on trees, and transform their enthusiasm into financial support for both public and private urban forestry efforts.

Bieg’s proposal landed on the desk of Greg Braswell, the information technology manager for the Department of Public Works. Braswell recognized that a mapping tool integrating the two forest databases would solve many problems for the city. The tool could help BUF become more efficient by making it faster and easier to access, update and share data with FUF, automating what has always been a paper- and labor-intensive process. The more accurate and complete data would allow BUF employees to manage trees more effectively, too, tracking the health of different species and seeing which thrive in the city’s many micro-climates. Funding and paperwork challenges could have killed the project from the start, but Braswell looked outside the city’s infrastructure and asked Autodesk to sponsor the project.

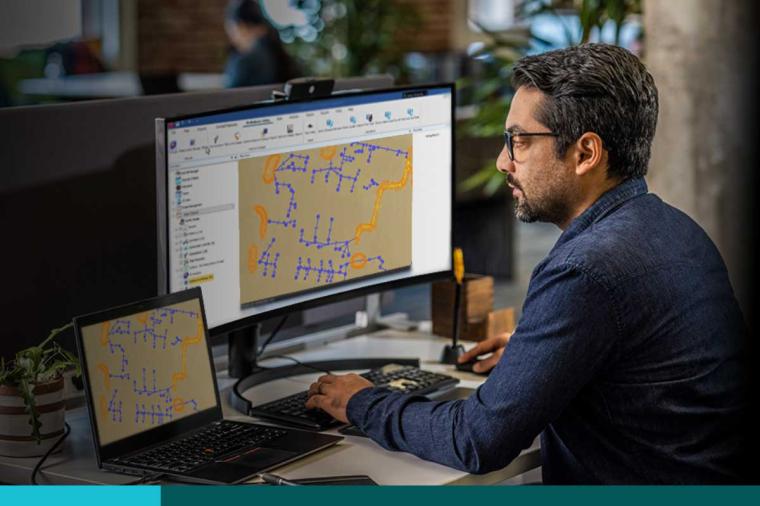

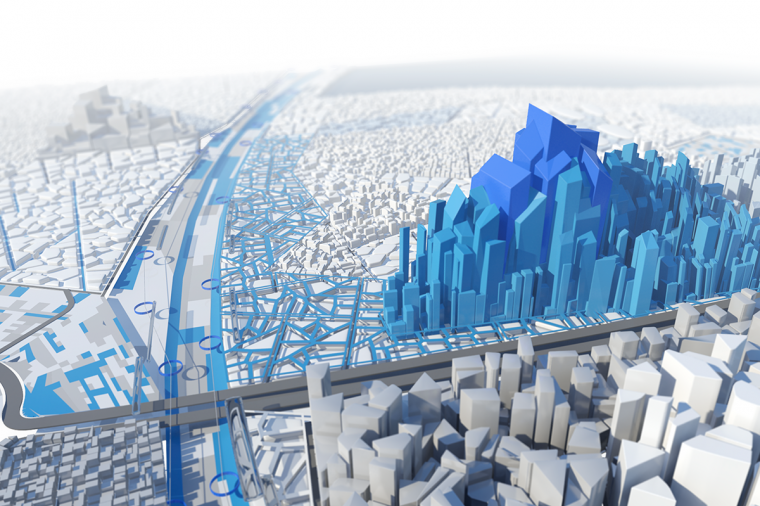

A few short months later, the San Francisco Urban Forest Mapping Project (www.urbanforestmap.org) was launched, funded by Autodesk® and developed by Online Mapping Solutions LLC of Santa Cruz, California. Based on MapGuide Open Source (mapguide.osgeo.org), the application integrates the BUF and FUF databases and displays a comprehensive view of the urban forest. The web interface lets BUF

and FUF employees, volunteers and members of the public quickly and easily access and update the city’s tree record. Searchable by street, species, planting date or organization, the tool gives professional and amateur urban foresters alike a window on their favorite arboreal assets. You can see the map at www.urbanforestmap.org/map/.

The application also links to other urban forest tools, such as the cost-benefit analysis software called STRATUM (Street Tree Resource Analysis Tool for Urban Forest Managers), developed by the USDA Forest Service Center for Urban Forest Research at the University of California, Davis. By quantifying the benefits provided by urban trees, STRATUM helps cities understand the impact of their forestry budget decisions.

Bieg’s vision calls for even more magic from the map – she sees a day when FUF volunteers and youth program members will use wireless handheld computers to upload a tree’s exact location, its photo and other updates[i]. The BUF database usually includes a tree’s street address, but not its x and y coordinates. Using the latest technology to enhance urban ecology will serve a social purpose, too – giving at-risk and low-income youth marketable skills in geospatial information systems and data analysis as well as in urban forest management.

And it doesn’t stop there. Because the mapping tool is based on open source software, the project team plans to share it freely with other cities and software developers, hoping to create a model that helps other public works departments everywhere manage their assets more effectively. Soon it will be easier than ever to become an urban forester, wherever you live. Now if someone could just map the best coffee shop closest to each tree, you’d be ready to go.

Originally published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 7

A few short months later, the San Francisco Urban Forest Mapping Project (www.urbanforestmap.org) was launched, funded by Autodesk® and developed by Online Mapping Solutions LLC of Santa Cruz, California. Based on MapGuide Open Source (mapguide.osgeo.org), the application integrates the BUF and FUF databases and displays a comprehensive view of the urban forest. The web interface lets BUF

and FUF employees, volunteers and members of the public quickly and easily access and update the city’s tree record. Searchable by street, species, planting date or organization, the tool gives professional and amateur urban foresters alike a window on their favorite arboreal assets. You can see the map at www.urbanforestmap.org/map/.

The application also links to other urban forest tools, such as the cost-benefit analysis software called STRATUM (Street Tree Resource Analysis Tool for Urban Forest Managers), developed by the USDA Forest Service Center for Urban Forest Research at the University of California, Davis. By quantifying the benefits provided by urban trees, STRATUM helps cities understand the impact of their forestry budget decisions.

Bieg’s vision calls for even more magic from the map – she sees a day when FUF volunteers and youth program members will use wireless handheld computers to upload a tree’s exact location, its photo and other updates[i]. The BUF database usually includes a tree’s street address, but not its x and y coordinates. Using the latest technology to enhance urban ecology will serve a social purpose, too – giving at-risk and low-income youth marketable skills in geospatial information systems and data analysis as well as in urban forest management.

And it doesn’t stop there. Because the mapping tool is based on open source software, the project team plans to share it freely with other cities and software developers, hoping to create a model that helps other public works departments everywhere manage their assets more effectively. Soon it will be easier than ever to become an urban forester, wherever you live. Now if someone could just map the best coffee shop closest to each tree, you’d be ready to go.

Originally published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 7

[i] Originally published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 7, 2008. Please look for more information on the Urban Forest Map in coming weeks!

A few short months later, the San Francisco Urban Forest Mapping Project (www.urbanforestmap.org) was launched, funded by Autodesk® and developed by Online Mapping Solutions LLC of Santa Cruz, California. Based on MapGuide Open Source (mapguide.osgeo.org), the application integrates the BUF and FUF databases and displays a comprehensive view of the urban forest. The web interface lets BUF

and FUF employees, volunteers and members of the public quickly and easily access and update the city’s tree record. Searchable by street, species, planting date or organization, the tool gives professional and amateur urban foresters alike a window on their favorite arboreal assets. You can see the map at www.urbanforestmap.org/map/.

The application also links to other urban forest tools, such as the cost-benefit analysis software called STRATUM (Street Tree Resource Analysis Tool for Urban Forest Managers), developed by the USDA Forest Service Center for Urban Forest Research at the University of California, Davis. By quantifying the benefits provided by urban trees, STRATUM helps cities understand the impact of their forestry budget decisions.

Bieg’s vision calls for even more magic from the map – she sees a day when FUF volunteers and youth program members will use wireless handheld computers to upload a tree’s exact location, its photo and other updates[i]. The BUF database usually includes a tree’s street address, but not its x and y coordinates. Using the latest technology to enhance urban ecology will serve a social purpose, too – giving at-risk and low-income youth marketable skills in geospatial information systems and data analysis as well as in urban forest management.

And it doesn’t stop there. Because the mapping tool is based on open source software, the project team plans to share it freely with other cities and software developers, hoping to create a model that helps other public works departments everywhere manage their assets more effectively. Soon it will be easier than ever to become an urban forester, wherever you live. Now if someone could just map the best coffee shop closest to each tree, you’d be ready to go.

Originally published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 7

A few short months later, the San Francisco Urban Forest Mapping Project (www.urbanforestmap.org) was launched, funded by Autodesk® and developed by Online Mapping Solutions LLC of Santa Cruz, California. Based on MapGuide Open Source (mapguide.osgeo.org), the application integrates the BUF and FUF databases and displays a comprehensive view of the urban forest. The web interface lets BUF

and FUF employees, volunteers and members of the public quickly and easily access and update the city’s tree record. Searchable by street, species, planting date or organization, the tool gives professional and amateur urban foresters alike a window on their favorite arboreal assets. You can see the map at www.urbanforestmap.org/map/.

The application also links to other urban forest tools, such as the cost-benefit analysis software called STRATUM (Street Tree Resource Analysis Tool for Urban Forest Managers), developed by the USDA Forest Service Center for Urban Forest Research at the University of California, Davis. By quantifying the benefits provided by urban trees, STRATUM helps cities understand the impact of their forestry budget decisions.

Bieg’s vision calls for even more magic from the map – she sees a day when FUF volunteers and youth program members will use wireless handheld computers to upload a tree’s exact location, its photo and other updates[i]. The BUF database usually includes a tree’s street address, but not its x and y coordinates. Using the latest technology to enhance urban ecology will serve a social purpose, too – giving at-risk and low-income youth marketable skills in geospatial information systems and data analysis as well as in urban forest management.

And it doesn’t stop there. Because the mapping tool is based on open source software, the project team plans to share it freely with other cities and software developers, hoping to create a model that helps other public works departments everywhere manage their assets more effectively. Soon it will be easier than ever to become an urban forester, wherever you live. Now if someone could just map the best coffee shop closest to each tree, you’d be ready to go.

Originally published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 7

[i] Originally published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 7, 2008. Please look for more information on the Urban Forest Map in coming weeks!