What Should Government Agencies Do When they Discover a Data Breach?

Data breaches are an unfortunate fact of life for government agencies – Edward Snowden being the most infamous case. And although agencies have taken steps to protect themselves, the growing number of breaches continues to frustrate IT and legislators alike.

According to a 2014 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), the number of security incidents involving personally identifiable information (PII) reported by federal agencies increased 10,481 incidents in fiscal year 2009 to 22,156 incidents in fiscal year 2012, an increase of 111 percent.

In 2014, for example, an IRS employee took home a computer thumb drive containing unencrypted data on 20,000 fellow workers and loaded the drive onto an unsecured home network.

State and local agencies are also vulnerable.

In 2012, more than 3.3 million unencrypted bank account numbers and 3.8 million tax returns were stolen in significant attack against the South Carolina Department of Revenue triggered by a phishing attack. An employee fell for it and opened the doors to hackers who were able to use the employee’s access privileges to access systems and database.

Federal Data Breach Reporting – Changes on the Horizon

Despite the increase in attacks, the GAO found that federal policy for collecting information and providing assistance to agencies on PII breaches has provided limited benefits. How can this be?

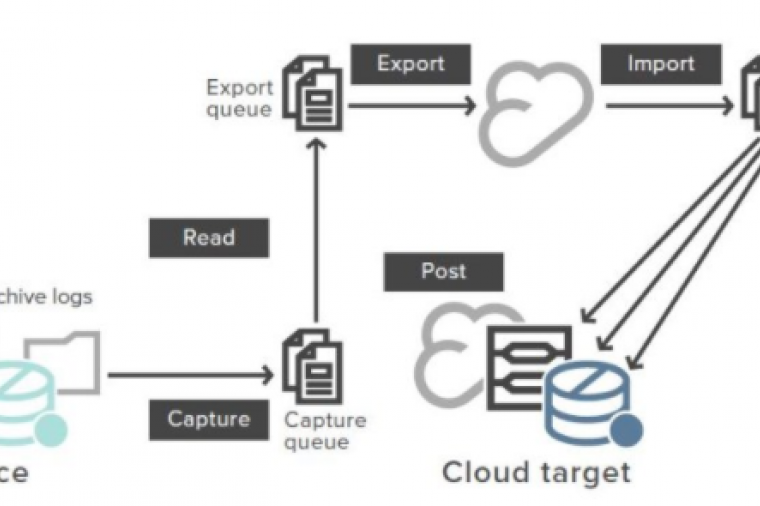

As it currently stands, OMB requires agencies to report each PII-related breach to the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) within one hour of discovery. The problem is it can take weeks if not months to compile this data. Preparing anything meaningful in the meantime just isn’t possible.

In light of these findings, GAO recently recommended that OMB revise its data breach reporting guidelines to "…better reflect the needs of individual agencies and the government as a whole and consolidated reporting of incidents that pose limited risk," reports Federal News Radio. So, expect to see new guidance from OMB later this year on the one-hour rule.

Existing Guidelines – In a Nutshell

Of course, the one-hour reporting requirement in only one part of the extensive legislation which agencies must wrestle with as they develop their response strategies.

There are also FISMA guidelines, FIPS requirements, and NIST guidance and standards, all of which are as outlined in OMB Memorandum M-07-16, Safeguarding Against and Responding to the Breach of Personally Identifiable Information.

As with all federal memos, it’s way too much to lay out here. However, by way of a summary, GAO has compiled a useful matrix of the key practices specified by OMB and NIST (refer to page 13 of this GAO document). These include:

- Establishing a data breach response team

- Train employees on roles and responsibilities for breach response

- Prepare reports in suspected data breaches and submit them to appropriate internal and external entities

- Assess the likely risk of harm and level of impact of a suspected data breach in order to determine whether notification to affected individuals is needed

- Offer assistance to affected individuals (if appropriate)

- Analyze breach response and identity lessons learned

A Word of Caution - Response Efforts can Often Lead to Bigger Problems

Clearly the days and weeks after a breach is realized are critical, but it’s also an emotional time writes Russell Roering in Symantec’s Security Insights Blog, and he offers up a few words of caution:

“There’s a tendency to want to turn on exhaustive logging, take servers offline, or even try to respond to the incident without knowing that you might be accidentally deleting evidence. The truth is doing these things can be counterproductive to forensic efforts at best, and could lead to bigger problems. The key is to understand the typical flow of actions to take in wake of a breach, incorporate best practices and have an incident playbook ready.”

While, in addition to OMB guidance, many federal and state and local agencies have their own guidelines for handling data breaches (albeit inconsistently implemented), Roering’s blog: What To Do-And What Not To Do-When You Discover a Breach offers some directional, not diagnostic, suggestions for how organizations can respond in the critical days and weeks following a breach. Roering also stresses the importance of an incident response program and crisis communication plan which includes other stakeholders, not just IT.

Of course every scenario is different, but as Roering points out: “…if organizations stick to guiding principles and develop playbooks for how to respond to certain types of incidents, they will be better prepared to combat them when they arise.”

photo credit: gruntzooki via photopin cc